"Do I dare to eat a peach?" T.S. Eliot lives!

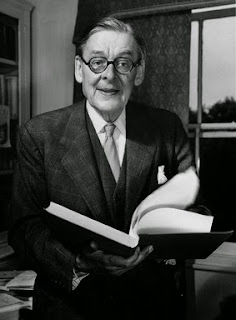

Starting the new year with a bang and not a whimper here's to T.S. Eliot! This week marks the 50th anniversary of Eliot's death in 1965; he lived to see the Beatles' first LP, but not a man on the moon. He also lived to see himself an esteemed figure, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, which he accepted, he said in his speech, "not on my own merits, but as a symbol, for a time, of the significance of poetry". Of course, that "for a time" was excessively modest, as is demonstrated by the flurry of activity the anniversary is engendering: readings, productions, broadcasts, a Mass or two, a social media shout-out with his own hashtag of #TSEliot, and more.

In a prime example, actor Stephen Dillane, who is described by the event organisers -- and here's where we see what 50 years mean -- with pride rather than offhandedness as "well known for his roles in Game of Thrones and Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince", will read Four Quartets in Bloomsbury, "just metres from the site of the original Faber & Faber offices" where Eliot worked for four decades and where, noted his colleague Frank Morley at Eliot's 60th birthday symposium, he drew attention above all for his talent at writing blurbs. Other tidbits which have come to light include the fact that Eliot turned down Animal Farm because he thought that, well, actually the pigs were the most qualified to run the farm, they just needed to have more public spirit (you can read the rejection letter on the Open Culture website).

Too, the prize money for the T.S. Eliot Prize for poetry was increased this year in honour of the anniversary, from £15000 to £20000; the yearly stipend the Bloomsbury group had wanted to put together so that Eliot could quit his earlier job at Lloyd's Bank was £500. Virginia Woolf and Co. were among the first to recognise Eliot's genius, though they also mocked his primness, with Clive Bell recalling, in his essay "How pleasant to know Mr Eliot", an invitation he received from Virginia which read, "Come to lunch on Sunday. Tom is coming and what is more, is coming with a four-piece suit." Eliot turned down the stipend, if not the lunch.

Lacked flamboyance

"Lacked flamboyance" was one of the subheadings in Eliot's obituary in the New York Times, where he is described as a "clerkish type", famed for his bowler and "tightly rolled-up umbrella". A clerkish colossus whose "The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock" ushered in the modern movement in poetry. In an Eliot 2-for-1, "Prufrock" also has an anniversary this year: its centenary. Its first appearance, in Harriet Monroe's Poetry magazine, was in 1915 -- the same year that Albert Einstein completed his General Theory of Relativity, ushering the concept of black holes, modernity in another form, into physics.It's hard to realise now, the extent to which people were put off by "Prufrock" a century ago. I remember reading the story (I think in someone's memoirs -- I've been trying to recall exactly where, to no avail; if anyone knows, I'd love to hear from you) of how a cultured society hostess invited Eliot to read it aloud at a luncheon she was giving, and how after the first lines the guests began dropping to their knees and crawling away, so that their impolite departures would be hidden by the tablecloths.

What was so shocking about "Prufrock"?

Let's hear it from someone who lived through those times. Desmond Hawkins, a disciple and a contributor to Eliot's review "The Criterion", decried in an essay for the 60th birthday symposium the "chumminess" and "sloppier sort of Romanticism" of the then-reigning Georgian poetry. But that was a minority view. By all accounts, 1915 was Rupert Brooke's year. His poems were quoted in the TLS, read from pulpits, collected, and published to great acclaim, in coincidence with his death on a hospital ship in the Aegean Sea on his way to Gallipoli, just a month before "Prufrock" was published in Poetry magazine.

Here's a verse from Brooke's collection:

Now that we’ve done our best and worst, and parted,

I would fill my mind with thoughts that will not rend.

(O heart, I do not dare go empty-hearted)

I’ll think of Love in books, Love without end...

And here's what another beloved poet of the period, Walter de la Mare, was writing:

Some one came knocking

At my wee, small door

Some one came knocking

I'm sure, sure, sure...

Here's a taste of John Masefield's famous "Dauber", which came out in 1915 as well:

Then came the cry of “Call all hands on deck!”

The Dauber knew its meaning; it was come:

Cape Horn, that tramples beauty into wreck,

And crumples steel and smites the strong man dumb...

and of Alfred Noyes's "The Lord of Misrule", another 1915 publishing date:

Your God still walks in Eden, between the ancient trees,

Where Youth and Love go wading through pools of primroses

And then, suddenly, there was this:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table...

the story of an everyday hell, made up of failures, doubts and disappointments, with an epitaph from Dante's Inferno in which Guido da Montefeltro swears to Dante that he will speak the truth, as there is no point in fabricating, given that none of them will make it out of hell alive.

Here is a great recitation of "Prufrock" by Anthony Hopkins, which I highly recommend. I've always found it difficult, as a mere mortal, to be convincing on some of those inflections, even in my head -- "Do I dare to eat a peach?" must be one of the most difficult lines to read aloud in the history of poetry -- so it's nice to have someone take command. He does it at a very fast tempo, which I wasn't sure about then and there, but which turned out to be a masterful intuition (more pain, less pomposity). See if you agree. Text follows so you can read along.

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

To lead you to an overwhelming question ...

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go and make our visit.

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes,

The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes,

Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening,

Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains,

Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys,

Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap,

And seeing that it was a soft October night,

Curled once about the house, and fell asleep.

And indeed there will be time

For the yellow smoke that slides along the street,

Rubbing its back upon the window-panes;

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

There will be time to murder and create,

And time for all the works and days of hands

That lift and drop a question on your plate;

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea.

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

And indeed there will be time

To wonder, “Do I dare?” and, “Do I dare?”

Time to turn back and descend the stair,

With a bald spot in the middle of my hair —

(They will say: “How his hair is growing thin!”)

My morning coat, my collar mounting firmly to the chin,

My necktie rich and modest, but asserted by a simple pin —

(They will say: “But how his arms and legs are thin!”)

Do I dare

Disturb the universe?

In a minute there is time

For decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.

For I have known them all already, known them all:

Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons,

I have measured out my life with coffee spoons;

I know the voices dying with a dying fall

Beneath the music from a farther room.

So how should I presume?

And I have known the eyes already, known them all—

The eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin,

When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall,

Then how should I begin

To spit out all the butt-ends of my days and ways?

And how should I presume?

And I have known the arms already, known them all—

Arms that are braceleted and white and bare

(But in the lamplight, downed with light brown hair!)

Is it perfume from a dress

That makes me so digress?

Arms that lie along a table, or wrap about a shawl.

And should I then presume?

And how should I begin?

Shall I say, I have gone at dusk through narrow streets

And watched the smoke that rises from the pipes

Of lonely men in shirt-sleeves, leaning out of windows? ...

I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.

And the afternoon, the evening, sleeps so peacefully!

Smoothed by long fingers,

Asleep ... tired ... or it malingers,

Stretched on the floor, here beside you and me.

Should I, after tea and cakes and ices,

Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis?

But though I have wept and fasted, wept and prayed,

Though I have seen my head (grown slightly bald) brought in upon a platter,

I am no prophet — and here’s no great matter;

I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker,

And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid.

And would it have been worth it, after all,

After the cups, the marmalade, the tea,

Among the porcelain, among some talk of you and me,

Would it have been worth while,

To have bitten off the matter with a smile,

To have squeezed the universe into a ball

To roll it towards some overwhelming question,

To say: “I am Lazarus, come from the dead,

Come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all”—

If one, settling a pillow by her head

Should say: “That is not what I meant at all;

That is not it, at all.”

And would it have been worth it, after all,

Would it have been worth while,

After the sunsets and the dooryards and the sprinkled streets,

After the novels, after the teacups, after the skirts that trail along the floor—

And this, and so much more?—

It is impossible to say just what I mean!

But as if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen:

Would it have been worth while

If one, settling a pillow or throwing off a shawl,

And turning toward the window, should say:

“That is not it at all,

That is not what I meant, at all.”

No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be;

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or two,

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use,

Politic, cautious, and meticulous;

Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse;

At times, indeed, almost ridiculous—

Almost, at times, the Fool.

I grow old ... I grow old ...

I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.

Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?

I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

I have seen them riding seaward on the waves

Combing the white hair of the waves blown back

When the wind blows the water white and black.

We have lingered in the chambers of the sea

By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

Yep, I'm with Desmond Hawkins who, looking back in 1948, summed it up like this: "Eliot restored the position of poetry as high art and not merely a capricious effusion".

The writer Robert Sward told the story ("All at Sea with T.S.E") of how, around the same time, a US Navy officer expressed what I think is more or less the same concept, though he used slightly different terms:

In 1952, sailing to Korea, a U.S. Navy librarian for Landing Ship Tank 914, I read T.S. Eliot's The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Ill-educated, a product of Chicago's public school system, I was nineteen years old and, awakened by Whitman, Eliot and Williams, had just begun writing poetry. I was also reading all the books I could get my hands on. Eliot had won the Nobel Prize in 1948 and, curious, I was trying to make sense of poems like Prufrock and The Waste Land.

"What do you know about T.S. Eliot?" I asked a young officer who'd been to college and studied English Literature. I knew from earlier conversations that we shared an interest in what he called "modern poetry." A Yeoman Third Class, two weeks at sea and bored, I longed for someone to talk to. "T.S. Eliot was born in St. Louis, Missouri, but he lives now in England and is studying to become an Englishman," the officer said, tapping tobacco into his pipe. "The 'T.S.' stands for 'tough shit.' You read Eliot's Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, what one English Prof. called 'the first poem of the modern movement,' and if you don't understand it, 'tough shit.' All I can say is that's some love song."

The officer talks him through the poem and then he says:

"At some level in our hearts, we are all J. Alfred Prufrock, every one of us, and we are all sailing into a war zone from which, as the last line of the poem implies, we will never return."

Fantastic article, and Anthony Hopkins....oh wow!

ReplyDelete